Cold emails, Dunbar numbers, and non-alcoholic beer

Sajith Pai's still irregular newsletter #34

Welcome to the 34th edition of my irregular newsletter. Since the last newsletter, published early May, we saw ~750 new subscribers sign up for the newsletter. Welcome aboard my new subscribers, and enjoy your first newsletter.

Quick housekeeping announcements for the new subscribers. The newsletter has two permanent sections: Writings - where I usually write and / or refer to one or more original pieces that I published in the previous months, typically about venture or the startup ecosystem, and Readings - about what I read and learnt about. My reading diet is tilted rather heavily in favour of books and podcast transcripts, and against articles / newsletters. This will naturally reflect in the reading list.

This is a long newsletter - think of it as akin to a monthly magazine from me (only the frequency may not be monthly!). I don’t know if you can read this entire newsletter (and peruse the links) in one sitting, and even if you do a second run ( which I very much doubt), you will have to pick and choose what to focus on. A good way to read this newsletter is to certainly read my original writing(s) below, and then glance through the rest and pick 1-2-3 items that pique your interest. Anything more is a bonus!

Writings

My AMA on Accel India’s SeedToScale website

I did an AMA for the SeedToScale website (run by Accel India). They crowdsourced 7 questions re the themes in the Indus Valley Report 2025. I answer questions across topics such as what the moats in the age of AI are, if India will become a manufacturing power, our perspectives on QCom, on how founders without traction or growth can access capital.

The episode is here:

The transcript of the episode is on my website.

Here is one of the seven questions and my answer:

So question number seven, traction versus capital chicken egg. Many early stage consumer tech founders face this paradox. VCs want traction before investing, but traction often requires upfront capital. What’s your advice for founders facing this?

So the secret of venture is that there are two types of founders and there are two types of venture funding mechanisms that have evolved to cater to these. So if you’re a second time founder, you don’t need traction. You’ve proven yourself through previous company founding. You’ve done well. Or even if you haven’t done well, you’ve shown that you have the requisite experience.

So typically, VCs are happy to fund second time founders on paper plans alone. And there’s a lot of money that can kind of flow into these founders. But if you’re a first time founder, yes, you do need to show some traction.

And yeah, you’re right in saying that if you don’t get access to funds, how will you show traction? So there are two bits of advice I have for you. One is figure out what stage of VCs you’re talking to. If you are a first time founder, then try and take some money from friends and family or angel investors who are happy to kind of fund you.

For example, you’re working in a high growth startup and you can ask the founder of that high growth startup; if it’s a unicorn, then even better because they would have had some liquidity, some outcomes, and they’ll be able to kind of give you some starter capital. Through that starter capital, you can build the business to a certain stage, you can show growth, and then approach a VC who’s relevant for that stage, like a pre-seed VC or a seed VC. And then this is the capital that you get, which gets you to the next stage, you can approach a Series A VC.

So I would say stage your capital raising requirements. Don’t come to a series A VC if you’re a first time founder with a paper plan idea. Very, very unlikely that you’re going to get funded.

Second, let’s say that you have growth, you have traction, but VCs are passing on you saying that’s not enough. So what should you do? What you can do is to research out which VC has an interest or a thesis in your sector. Don’t approach every single VC. Go find out who those specific VCs are and build a relationship with them. Because they believe in your sector, in the problems that you’re attacking, and they have a thesis in that sector, they have a prepared mind, and they may be willing to take a risk. They may say that, hey, sure, we would have ideally liked this revenue, but, you know, willing to take the chance on you.

So you need one VC to say yes, right? So these are the two bits of advice I would tell you to solve the capital versus traction chicken egg problem.

The best VCs are long preloaded context windows for their founders

Short piece on how the best VCs continually update their knowledge of the company, the people, its challenges (effectively context about the company) so that founders reduce time to query on key decisions. Without the context, the founder has to spend a lot of time setting the context with the VC, thus taking time. The best VCs have the company context ready in their minds thus saving the founder time, and increasing the chances that founder will reach out to them over another VC.

Link to the piece. (Originally published in newsletter #32)

Readings

Books

I completed four books, and left more than a few unfinished. Some of these will be permanently unread but there are a few I will get back to completing. One reason is that I am not able to read in chunks due to lack of time. A lot of reading time is really on weekends. That means if I read 50-100 pages on weekends, then I have to wait till the next weekend for the next 50-100, and then the challenge is that I have lost context. My present reading style thus lends itself to shorter books that I can read over a weekend across 2-3 sittings (books 2-4 in the below list were all read over a day / weekend), or something I can read for 30-45 mins daily such as a book of short stories or a non-fiction book with short independent chapters, e.g., Burkeman’s book below. Janan Ganesh refers to this in a piece sharing reading advice: “Don’t read fewer than 50 pages in a sitting. The cost of pecking at a book here and there is a lost sense of its narrative wholeness. (“If you read a novel in more than two weeks, you don’t read the novel” — Philip Roth.)”

Here we go.

Meditations for Mortals - Oliver Burkeman

Those who have read Oliver Burkeman's previous book, the best-selling 'Four Thousand Weeks' will find a lot that is familiar. The key theme of 'Four Thousand Weeks' (so called because that is the average life span) is that life is short, and you can't do it all, and you need to choose a few and enjoy them. That advice is carried over here as well and informs many chapters of this book as well. In addition there is a related theme of how we try to create productivity systems and processes when all we need to do is just start doing stuff. Then there are a few practical tips, all around the theme of not trying to stufff your day with tasks, and not building your life around productivity systems such as working on creative pursuits 3-4 hrs a day tops, sticking to a dailyish schedule (not the Seinfeld Strategy of 'not breaking the chain'), treating your to read list like a river not a bucket, that is, dip in and out, and dont feel forced to read something; and so on. Overall a decent read, and will appeal especially to those who like to dip into productivity porn.

Link to my summary of the book.

Paper Belt on Fire - Michael Gibson

Not as well-written or as well-edited a book as I expected; one that could have been much tighter, though still relevant as a history of the Thiel Fellowship and the 1517 fund, the largest student-focused venture fund. As a venture nerd, I found the book interesting enough, with a glimpse into Peter Thiel's thinking and way of working as the highlight, but to those outside (especially those with no axe to grind re U.S. culture wars), it may not be as useful / interesting.

All In: Memoirs of the Freshworks Founder - Girish Mathrubootham w Pankaj Misha

Girish Mathrubootham, one of the central figures in the Indian startup sphere, thanks to his founding of Freshworks, as well as pioneering the key community initiative SaaSBoomi, shares his backstory, covering his childhood (mentions but doesnt dwell too much on his parents' divorce, which was rare for that era in India), his attempts at early entrepreneurship teaching Java, his growth at Zoho, and then the founding and scaling of Freshworks. It is a wonderful portrait, raw and honest on several fronts, but ultimately a tad unsatisfying. I think it is because the best businesse (auto)biographies have the qualities of what Girish preferred in SaaSBoomi talks - anecdotal, authentic, and actionable. While this autobiography is anecdotal, and authentic, it falls short of having any actionable insight. That perhaps is why I found it a tad bit unsatisfying. Still, full credit to Girish for authoring this, and being vulnerable. More and more Indian startup founders should author their memoirs. One I would certainly like to read is Sanjiv Bikchandani's.

Alpha Girls - Julian Guthrie

Julian Guthrie covers the story of four women VCs, and the challenges they face as they navigate their careers and straddle professional + personal lives. Very candid, and empathetic portrait. Venture nerds will enjoy this (lots of fun stories incl how the Facebook deal was done, the early days of Salesforce etc.) Must read for women investors, their bosses, and their husbands; for the picture that is painted from these portraits is not a pretty one. It says that the husbands and bosses / partners dont always support their ambitious women, and this makes it tough for women to juggle these multiple roles.

Articles

1/ Lenny Rachitsky: To write consistently, write only what you are curious about

Link to article.

Lenny: “…Initially, my heuristic was 80% writing about what I’m energized/curious/excited to write about and 20% writing about what people want me to write about. These days, it’s actually 100% what I’m curious about. I now never publish anything only because I know it’ll do well.

This is actually a very important lesson I’ve learned: In this line of work, individual (viral) posts come and go, but it’s all about how long you can stick with it. One viral post: easy. One post every week for five years: much less easy. You need to prioritize stamina over anything else. In other words, play ‘infinite games’.”

2/ Elliot Jaques’s time horizon – strata fit

Link to article.

Beginning to see Elliot Jaques pop up off and on, most recently on the Roelof Botha episode with Mario Gabiele / The Generalist (see above). Here is an excerpt from an old but good piece on the social scientist. (He passed away in 2003)

Art Kleiner: “But if everyone agreed on the value of jobs, what did that value depend upon? Dr. Jaques was stumped until, one morning, three shop stewards burst in to tell him they’d figured it out. The critical difference had to do with time. Factory floor operators were paid by the hour, junior officers by the week, managers by the month, and executives by the year. Within two years, Dr. Jaques had refined this insight to the concept of “time span” — the value of every job could be measured by the length of time it took to carry out its longest-running assignment. (He also called it a “by-when,” his name for the explicit or implicit deadline embedded in every task.) A maintenance operator on a factory floor might wrap up all tasks within a 24-hour period, but a purchasing manager might need up to three months to finalize a contract, and a marketing VP might take two years to plan and implement the introduction of a new soap. The longer the time span, the greater the amount of “felt-fair pay” that was appropriate to earn.

In the early 1980s, he codified his findings. The true fit between a person and a job, he has concluded, depends on the match between the “time span” of the job and the potential capabilities of the person.

At the heart of the Jaques work is this double helix of human capability in organizations. On one side of the helix are the “categories” (as Dr. Jaques calls them) of people’s ability to handle cognitive complexity. Each of us is born with a certain potential ability to handle complexity. By the time we come of age (at, say, 18), if we’ve matured to that potential, then we can handle assignments of three months, a year, two years, five years, or more. This “time horizon” is more or less hardwired into us (not just in our minds, but in our beings, Dr. Jaques would say). Some people start out higher than others. On the bright side, we all continue to mature all our lives, making occasional palpable leaps in our ability about every 15 years, as we cross a threshold into the next level of capability. (If you realize that you can suddenly handle tasks that seemed unfathomable before, you’ve probably made such a leap recently.)

Of course, we may not fulfill our potential; we may be blocked by (for example) a physical accident like a stroke, the kind of emotional baggage that leads to neurotic self-destruction, a decision simply not to strive for success, or sheer lack of opportunity to develop our skills — which is one reason hierarchies are so important for many people.

That brings us to the other side of the double helix. Just like the time horizons (for people), the time spans (for jobs) break naturally, according to Dr. Jaques, into eight levels, which he calls “strata.” The fit between time-horizon levels and strata determines how comfortable we will feel at various positions in a hierarchy.”

3/ Dwarkesh Patel asks what is to AI as the motor car was to petroleum

Link to article.

Dwarkesh has been trying to sensemake developments in AI through his eponymous podcast. In this article, he lists down all the open questions in his mind. I didn’t really understand all of the points (truth!) he raised. Still it was very useful to get a glimpse of his mind and what he sees as the big unsolved questions. Re his query on the industrial-use case of AI (what is the motorcar for AI’s fuel?), I am reminded of Tim Harford’s book ‘Fifty Things That Shaped the Modern Economy’ and the chapter on the dynamo. He writes how the old factories were all based around steam power and needed a central driveshaft to relay steam power. It was only when newer factories / layouts replacing the driveshaft with wires to individual workstations was enabled that electricity’s power could be used by every worker. Today perhaps it is the other way around. AI can be accessed by individuals easily but it perhaps need group or org adoption for its power to be fully realised.

Dwarkesh:

“What is the industrial-scale use case of AI? Between 1859 (when Drake first discovered oil in Pennsylvania), to 1908 (when Henry Ford invented the modern automobile), the main use for crude was as kerosene for lighting. What is the ultimate industrial-scale equivalent use case for AI?

*

How transformative would the AIs of today (March 2025) be even if AI progress stopped here? I’ve personally become more bearish about the economic value of current systems after using them to build miniapps for my podcast: I can’t give them feedback that improves their scope or performance over time, and they can’t deal with unanticipated messy details. But then again, the first personal computers of the 1980s weren’t especially useful either. They were mostly used by a few hobbyists. They had anemic memories and processing power, and there just wasn’t a global network of applications to make them useful yet. Another way to ask this question: imagine that you plopped down a steam engine in a hamlet from 1500. What would they do with it? Nothing! You need complementary technologies. There weren’t perfect steam engine shaped holes in these hamlets; similarly, there aren’t many LLM-shaped holes in today’s world.”

4/ Jake Knapp + John Zeratsky on the Founding Hypothesis

Link to article.

Jake Knapp who came up with the Design Sprint methodology, teams up with Jake Zeratsky to write how founders can lay out your pick or approach into a framework they call a founding hypothesis, which asks them to list out the problem they are going after, the likely customer, the approach, and finally their differentiation (see image below). It is a handy way to structure the startup idea, and forces clarity early on. The article also has a few more bells and whistles, including the process of running a ‘Foundation Sprint’ to structure the pick better and arrive at a common language and buy-in for all founders. Certainly worth a read, especially for early stage founders.

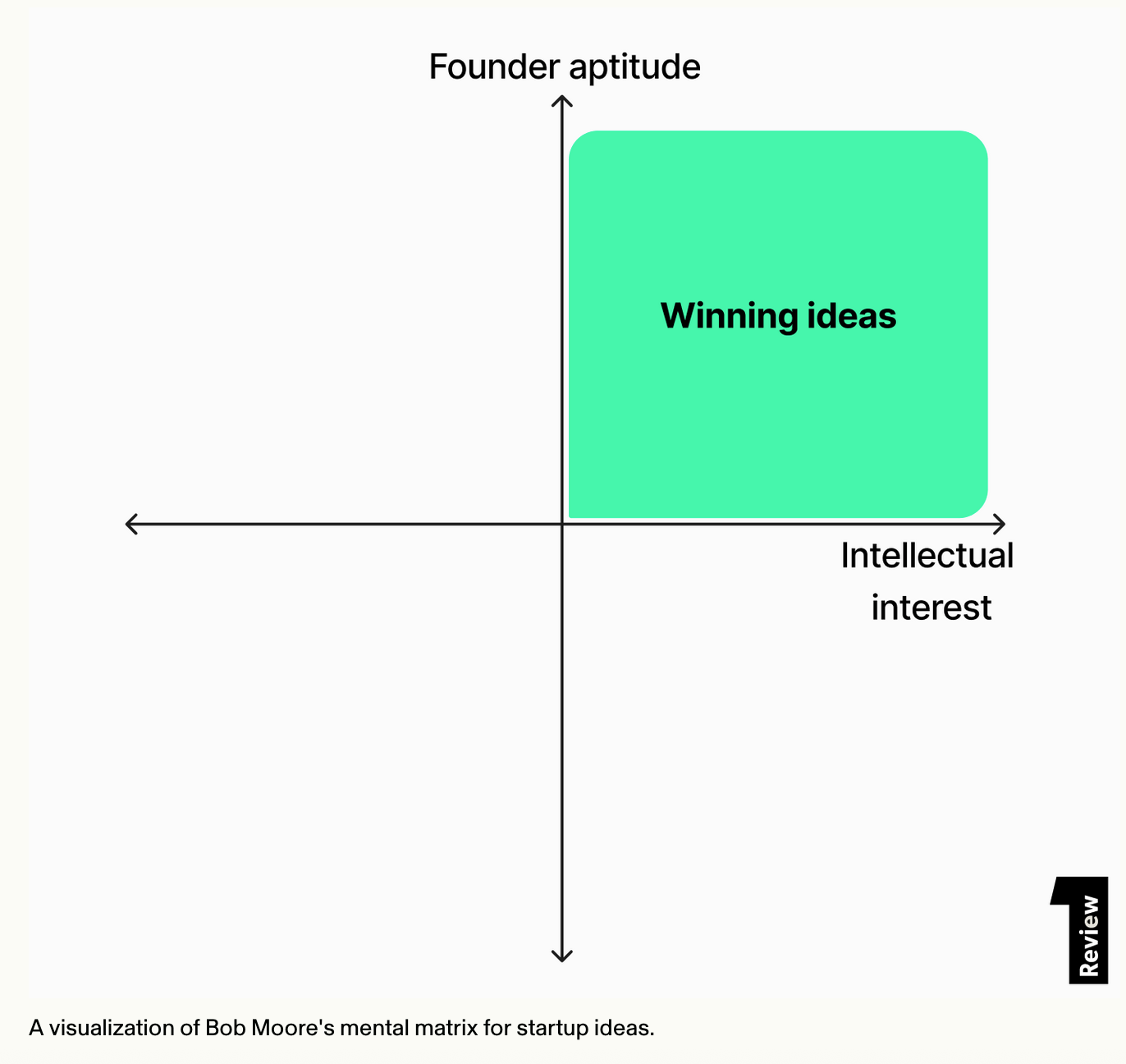

5/ Bob Moore, Crossbeam, on picking the space to play in

Link to article.

Third-time founder Bob Moore covers why his older ventures failed, and why the last one has a fighting chance of success, in this article. Has a detailed section on how he and his cofounder arrived at the startup idea looking at both their affinity for the space, as well as ability to win in the space.

“First, he had to whittle down his list of roughly 100 miscellaneous entries — which ran the gamut from B2B SaaS tools to an escape room franchise.

Too often, founders — especially those earlier in their careers — fail to take their own strengths into account when choosing an idea, merely chasing market trends or their own passions. When Moore started RJMetrics, he and Stein were fresh off a two-year stint in venture capital, hungry for a startup of their own. But when they quit their investor day jobs to get RJMetrics off the ground, they didn’t have a strategic game plan beyond wanting in on the heating-up analytics Market. “We went in as mercenaries. We wanted in on this startup game and big data was increasingly a thing. I knew how to write a damn good SQL query. But that was all we had,” says Moore.

Looking back on it now, Moore thinks one of the contributing factors to RJMetrics’ shorter shelf-life was that the founding duo lacked a sense of where the market was headed. “When we started RJMetrics, I didn’t have strong conviction. It may have been something that lit up my brain, but I didn’t even know the word ‘dashboard’ until after I started the company. We didn’t know business intelligence as a market — we didn’t even know who Gartner was,” he says.

Years into building RJMetrics, this absence of a long-term vision became glaring in the product strategy. “Because we weren’t steering with a solid strategy, we pursued all these product micro-optimizations and landed ourselves in a place where we created a company that creates some value for some people. Our growth was stuck on a local maximum. RJMetrics became designed by committee. We didn’t have a core conviction that a certain specific thing ought to exist because that’s where the market was going. That wasn’t there,” says Moore.

So when Moore was assessing ideas for his third startup, he knew he needed to be honest with himself about not only what he was excited to build, but what he was uniquely positioned to build well, given his chops as a multi-time SaaS founder. To do that, he devised a simple founder-market fit pre-screen — a mental matrix with two dimensions of interest and ability:

• Intellectual interest in the problem. How much fun would I have doing this? How much would it light up my Brain?

• Founder aptitude. What is it about my specific experience that makes me predisposed to being good at solving this problem?

“This helped Moore quickly rule out the oddball ideas and pipe dreams. “This exercise took my list of 100 down to 10 or 15 ideas,” he says. With the remaining handful of ideas that landed in the top right quadrant of his mental matrix, Moore wanted to get some outside opinions. But he chose to do things differently for the validation step: He bypassed the classic customer-driven discovery model and instead ran his remaining ideas past fellow founders.

Moore felt that founders could offer more nuanced perspectives — and widen any preconceived notions he might have had about each of these ideas. “Founders are special. They need to develop an extremely high level of empathy and understanding for the needs of people across multiple personas, and also understand a baseline grasp on how markets evolve over time and what makes for something that’s more durable and versatile,” he says.

With the founders, I wasn’t asking, ‘Would you buy this?’ But instead, ‘Would you start this company? And what are the things that you think you might bump into?’ “Rather than narrowing these ideas down into the scope of how a persona would use it, I was able to broaden my horizons of what they could become,” says Moore. “I wasn’t interested in having my next thing be anything other than an IPO-scale business — I wasn’t optimizing for a ‘build it for a few years and sell’ situation. I thought I had one more startup in me and I wanted to see how far I could take it.”

6 / The ultimate cold email / cold outbound handbook

Link to article.

This looong piece by @MattRedler on setting up a cold email / cold outbound strategy is excellent; easily amongst the best pieces of writing on this topic. It is also amongst the best examples of content marketing I have seen. Lots of detail on subtopics such as setting up adjacent domains, how many domains to buy, setting up SPF / DMARC / DKIM, warming your inboxes, who to send to, how to write emails etc., like here

“Most great cold emails do have the following elements in them, not necessarily in this order:

• Personalization

• Strong claim

• Evidence for that claim

• A clear next step

• Shorter than ~200 words

Include all of these in your email and you are, probably, Golden.

The most important piece to clarify here is “Personalization”: lots of people have the idea that this means opening your email with a line like, “Hey, I loved your post on LinkedIn last week!”

And while sometimes personalization might mean a cheesy line about LinkedIn, what’s important is that there is something in your email that makes it feel 1:1. People, more these days than ever, have their mental spam filter on when they get an email from a stranger. If there’s nothing in your email that indicates it’s personal and not a template sent to 1000s of people, you’re probably getting sent straight to trash and possibly marked as spam.”

Here are excerpts from the handbook / article I found interesting. Link.

7/ How consumer brand startups Arata, Fashor, Atomberg scale capital-efficiently

My colleague Rohit Kaul spoke to the founders of Arata, Fashor, and a founding team member at Atomberg – 3 companies across different points of scale to extract learnings.

Link to article.

Given my early stage focus, the lessons from Arata and Fashor resonated a bit more. Three that stood out to me – Arata founders on de-aggregating product performance by channel and aligning marketing comms per channel basis what is working, and how they use the Reason to Believe framework to create their performance ads, and Fashor’s founder on how they tease apart blended CAC to new user CAC and repeat user CAC and how that informs their customer acquisition strategy.

One of Arata’s most important discoveries was that product performance varies dramatically across channels. Bhasin explains, “My top products on quick commerce aren’t the same as on Amazon. Amazon’s top products aren’t my website’s top ones. There’s an overlap, but a visible top product difference across channels.”

This insight led them to analyze data more granularly and link it to custom messaging on different channels. Instead of pushing the same messaging across all platforms, they optimize marketing for each product’s best-performing channel.

“Say a shampoo is my top seller at the aggregate, business level but it may not be the top seller on quick commerce,” notes Bhasin. “But if your marketing spends and overall share of voice or brand voice, is targeted towards that shampoo, you won’t be able to optimize and make most of that specific channel.”

*

Their performance marketing is based on the Reasons to Believe framework.

“There’s a Reasons to Believe (RTB) sheet. What is the product? What is its USP? What are the ingredients? What are the benefits? How do the ingredients support those benefits and USP? What is the visual representation? What is the sensorial representation?”

Based on this RTB framework, Arata has developed a scientific approach to performance ads. “We’ve broken performance ads down to a science—what to appear in the first three seconds, in six seconds, eight seconds, all the way to 15 seconds,” explains Bhasin. Each segment serves a specific purpose: the first three seconds need a strong hook “to get the consumer to stay, stop scrolling, and watch the ad.”

“The core message will remain the same, but each platform needs specific adaptations,” Bhasin explains. “Amazon requires wide backgrounds, while Flipkart and Myntra allow strips calling out product benefits. The A-plus content (product page) remains similar across channels, just adapted for different specs and sizes.”

Once they know what’s working, they double down using the “double diamond strategy.” As Bhasin explains, “You find what’s working — which creative, which campaign, which tagline. Then you create two more underneath it and again test. So you continuously keep building on what’s working and keep shifting out what’s not working.”

*

Underpinning Fashor’s capital efficiency is a sophisticated approach to metrics tracking, focusing on data that directly informs profitability:

Segmented CAC: “We split our new customer CAC and repeat customer CAC on an everyday basis. You have to split. Don’t just look at blended CAC.”

This separation is critical for managing unit economics. “On repeat customers, you need to make a profit. You know your gross margin and variable costs… So you have to ensure your performance marketing cost generates a profit for you.”

New customer acquisition requires investment: “On new customers, initially there will be a burn, because new customer CAC is higher.”

The investment decision is strictly based on expected returns. “We accept the burn because we know over 40% of our customers repeat, and we know their frequency and lifetime value. As long as the LTV to CAC ratio is above 6x, we’re happy to invest in acquiring new customers.”

8 / Reducto’s Path to PMF

Link to article.

This is another of the Path to PMF series that First Round Review (an online site from storied seed fund First Round Capital) puts out. Each post takes the reader through the journey of a company and how they found PMF or Product Market Fit. I found this piece particularly interesting as it is a great example of how lukewarm reaction to their initial product (a long-term memory solution for language models) persuaded the founders to rethink their initial approach, and take up a new approach (making it easy to extract data in the right manner from PDFs), one which came from carefully listening to what their potential customers were asking. If you have read Mom’s Test or heard of the importance of problem validation, well, there is no better example. TLDR: It is either hell yes, or no.

“Hundreds of folks asked to be onboarded to the product, then called Remembrall (“Harry Potter” fanatics will notice a pattern with these company names), but early onboarding calls hinted that they were a bit too early to the space.

They had conversations with enthusiasts who would maybe try adding it to their AI application. “It was never the case where people were saying, ‘I’ve noticed that customers get angry at my product because X, Y, and Z and Remembrall can fix it.’ That was the first signal. The second signal was that people were maybe willing to pay $10-20 a month because they found the idea interesting. But no one’s product team needed it,” he says.

We set up demo calls with everyone who expressed interest and we asked what their use case was and what problems the product would solve for them. And we would very rarely get a real answer. It was more of a ‘This seems cool’ curiosity.”

…

“One of the most common feature requests for Remembrall was, ‘Hey, you’re managing my user’s chat history, can you manage the files that they’re uploading as well?” Abraham says. “We went into our projects expecting to help teams with fun ML problems, but very quickly learned that one of the biggest bottlenecks across most pipelines was actually well before retrieval or generation.”

So the co-founders built a very simple solution — they would upload the docs, parse them using an external parsing solution, and then chunk the information for you. “It’s embarrassing to look back on it now, it was a very ugly Streamlit app with a super simple document segmentation tool. It would do nothing other than split your documents into little boxes of content. I can’t stress this enough — it was literally a weekend project that we threw together,” says Abraham.

But they posted it on YC’s forum anyway, and the response was immediate and overwhelming. “We started getting replies, ‘This is better than what I’m getting from Textract. Is this a hosted API? Where’s the Stripe link?’ The pull was much stronger than everything else we had worked on,” he says.

…

Unlike the “seems cool!” enthusiasm for extended LLM memory, there was a distinct need and a massive pain point. “These companies are not trying to spend many hours of engineering time on PDF processing, but it’s the bottleneck that’s stopping them from building the things that actually matter. If we can be that ingestion team for our customers and take that problem off their plate, that’s clearly very valuable,” he says.

We had spent enough time exploring things that were not resonating. In comparison, it felt like we were getting punched in the face by this new idea — it was something people cared about an order of magnitude more.”

9/ Your ICP (Ideal Customer Persona) should be uncomfortably narrow

Link to article.

Good read with a lot of examples on how the likes of Vanta, Clay (see below), Webflow etc., all iterated towards their ideal customer persona or ICP; essentially the specific target persona the product is aimed at. The core mantra is that early on, your ICP should be uncomfortably narrow. As the article puts it: “It should be so narrow that when you describe what you’re building to friends and who it’s for, they think you’re slightly crazy for trying to do something so niche.” Subsequently as you hit product market fit and raise more funds, and you can widen the ICP aperture, and expand your feature set to cater to the wider ICP. But early on, keep it uncomfortably narrow!

“Clay is a tool for connecting APIs to your spreadsheets to enrich your data, and everyone wanted a piece of it. Recruiters told founder Kareem Amin how useful the product was for finding candidates. Salespeople wanted to use the platform for their inbound and outbound leads. Front-end engineers could use the spreadsheet as a low-code backend.

All this interest might sound great, but five years in, revenue was still hovering near zero. The warning signs were there when the initial spark died off quickly. “People would feel excited by the possibilities the product opened. But they weren’t always going back and using it the next day,” Amin told us. “So actually we had a lot of, ‘Wow, this is so powerful!’ and then no usage, or inconsistent usage.”

The Clay team accidentally cast too wide a net by building features every prospect wanted. As Amin explains it: “When you’re an early startup team, one of your strengths is that you’re malleable. A prospect can say, ‘Oh, could you guys do this?’ or ‘Are you guys this?’ And then you can become that, quite easily. What I’ve learned is that you have to know when to be malleable,” he says. “You can’t be changing the value prop or even the product itself from meeting to meeting. When you narrow the scope, it feels claustrophobic. Why are we doing something that’s smaller when we could be doing something bigger? Eventually, we realized that by narrowing down our scope, we were actually increasing our value.”

Finally, to escape the everything-to-everyone trap, Amin called a bold play: pick one specific ICP and go all in. They started with outbound sales teams.

“It wasn’t so much that I was 100% sure that outbound was the right call, although it was a faster starting point because all companies need it, versus typically only bigger companies needing inbound support, ” says Amin. “It was more that I realized we need to pick one thing at a time, test it out clearly and get feedback that we can react to quickly. That’s when we’d earn the right to execute on the more expansive parts of our mission.”

10 / The story of Founders Fund

Link to the story series page (paywalled).

Mario Gabriele’s quartet on Founders Fund (long enough to be a short book!) is utterly riveting. He covers its origin story, its distinctive philosophy, its polarising approach, and impact on the ecosystem, and how it is set up for selective but all in bets such as Palantir, Anduril, SpaceX, Ramp etc. There isn’t a fund like this, and perhaps never will be.

Podcasts

1/ Marc Andreessen doubts whether AI will disrupt early-stage VC

Link to podcast.

A little late to this podcast. Nothing special as such in the podcast, though this passage, on why he thinks early stage VC will not be significantly affected by AI, stood out. I quite agree. Early stage venture is all about identifying talent and picking people. It is also a place where in picking people you have to sometimes cast off past patterns / not be prisoners of patterns. My colleague Karthik said once: “Venture is a pattern-matching business, but the only stories worth telling are those built by exceptions”. Even if AI becomes the best pattern matcher, it will assign those weights and biases to past patterns. Yes, you can program it to reduce those weights and biases, and assign more importance to present context / state, but humans will still for a long while, be the best real-time weighers of state, context, and past patterns all together at once.

“Marc: What I’m about to say may just be wishful thinking on my part. I might be the last Japanese soldier on the remote island in 1948 by saying what I’m about to say. I’m going to attempt fate. But I’m going to say, look, so much of what we do on the early side in the first five years is really very deep evaluation of individual people, and then it’s working with those people in very deep partnership. And this is one of the reasons, by the way, that venture doesn’t scale well, particularly venture doesn’t scale well geographically. The geographic scale experiments tend not to work. And the reason is just because you end up having to be face to face with the people for a long time, both during the evaluation process, but also during the building process. Because in the first five years, these companies generally aren’t on autopilot. You actually work with them a lot to help make sure that they do the things that they’re going to need to succeed. There’s a part of this that is very, very deep. Interpersonal relationships, conversations, interactions, coaching, by the way. We learn from them, they learn from us. It’s a lot of back and forth. We don’t come in with all the answers, but we have one lens because we see a panorama. They have another lens because they’re in the specific details a lot more than we are. And so there’s tremendous interpersonal interaction that happens. Tyler Cowen talks about this, I think he calls it project picking.

Certainly talent scouting would be another version of this, which is basically like, if you look back over hundreds of years for any new area of human endeavor, you almost always have this thing where you have very idiosyncratic people who are trying to do something new. And then there’s some professional support layer of the people who fund them and support them for the music industry. That’s David Geffen finding all the early folk artists and turning them into rock stars. Or it’s David O. Selznick finding the early movie actors and turning them into movie stars. Or it’s the guys sitting in a cafe, a tavern in Maine 500 years ago, figuring out which whaling captains are going to be able to go get the whale there. You know, it’s Queen Isabella getting the pitch from Christopher Columbus in the royal chambers and saying, yeah, that sounds plausible. Why not? There’s this alchemy that has developed over time between the people who do the new thing and then the people who sort of enable, support and fund those people. Let’s just say, like, there’s no guarantee that this continues, but that’s like a 400, 500 year endeavor, honestly. Probably it’s thousands of years old. You probably had tribal chieftains 2,000 years ago, 3,000 years ago, sitting around a fire, and the young warrior would come up and say, I want to go take a hunting party into this other thing and I want to see if there’s better game over there. And the chief sitting around the fire trying to figure out whether to say yes or no. So there’s something very human about that. My guess would be that that continues. Having said that, if I meet the algorithm that can do that better than I can, I will instantly retire. We’ll see what happens.”

2/ Roelof Botha on the two trackers they send out every week at Sequoia

Link to podcast.

Good podcast, though for regular Sequoia-watchers, some of the content is a repeat of what they have heard / read. To me, as a VC here in India, what stands out is Sequoia’s obsession to enhance themselves in every aspect of venture craft, from access (by leveraging AI) to better picking by honing their decision-making through a) recognising cognitive biases + structuring their dealmaking process to factor these biases in, as well as b) combating these biases by using cognitive decision-aids such as their monday trackers etc.

Roelof: “We have an internal tracker here at Sequoia. We send it out every Monday as a reminder to be rational and level-headed as we look at late-stage private companies.

There’s about 690 public tech companies that we include in this basket. And we look at the current median multiple, enterprise value to revenue multiple, of this entire basket of companies. And right now, it’s sitting at the 60th percentile of the last two decades….in addition to that particular tracker, we have a sheet that we hand out that summarizes all the investments we’ve made to date in the current fund that we’re investing. And it’s a useful way to just reflect on what is the quality of the companies we’re assessing today. How does it measure up to the companies we’ve agreed to invest in?

And admittedly, there are mistakes in there and there’s some good decisions in there. But it’s a useful mechanism because humans are very good relative decision makers. Now, I’ve read some interesting behavioral economics research on this, where if I show you three different homes, and two of them are Spanish and one of them is Tudor, you’ll probably pick the nicer of the two Spanish homes just because you have a comparison.

If I showed you one Spanish and two Tudors, you might choose the nicer of the two Tudors. And so humans are just a little bit stuck in this relativism in how we make decisions. And so if you can widen the aperture of things that you put in that consideration set, I think it helps you make better decisions.

“Otherwise, you might just think about how good is this company relative to what else we’re looking at today or what else we’ve seen in the last month. You step back, you look at a wider set and it helps you really think about what quality means. Does this company have the potential to become a legendary company in the Sequoia language?”

More excerpts of what I found interesting here.

3/ Varun Mohan, Windsurf AI, on the changing role of the software engineer

Link to podcast.

Good read / listen for context-gathering around understanding how a AI-native high velocity startup founder thinks and executes (though I didn’t find anything dramatically new). His view on AI and coding in the light of GenAI’s rapid improvements in coding were interesting. Broadly 1/ Engineer’s role moving from coding to reviewing. 2/ Alpha in coding now moving to prioritisation / what to build (now what does this imply for PMs?!)

Varun: “One of the key pieces that we recognized was, with this new paradigm with AI, AI was probably going to write well over 90% of the software, in which case the role of a developer and what they’re doing in the IDE is maybe reviewing code. Maybe it’s actually a little bit different than what it was in the past.

…

The goal of AI has now changed a lot in that it is now modifying large chunks of code for you. And the job of a developer now is to actually review a lot of the code that the AI has generated.

…

I think when we think about what is an engineer actually doing, it probably falls into three buckets, right? What should I solve for? How should I solve it? And then solving it. I guess everyone who’s working in this space is probably increasingly convinced that solving it, which is just the pure, “I know how I’m going to do it” and just going and doing it, AI is going to handle vast majority, if not all of it.

In fact, it probably actually, with some of the work that we’ve done in terms of deeply understanding code bases, how should I solve it is also going to get closer and closer to getting done. If you deeply understand the environment inside an organization, if you deeply understand the code base, how you should solve it, given best practices when the company also gets solved.

So I think what engineering kind of goes to is actually what you wanted engineers to do in the first place, which is, what are the most important business problems that we do need to solve? What are the most important capabilities that we need our application, our product to have? And actually going and prioritizing those and actually going and making the right technical decisions to go out and doing it. And I think that’s where engineering is probably heading towards.”

4/ Robin Dunbar of Dunbar’s number fame, on the different relationship numbers that govern your life

Link to podcast.

Robin: “So you have these series of layers going out from you, which increased in size, but the quality of the relationship and the frequencies that you contact them gets smaller and smaller, smaller, lower and lower as you go further out. So these layers occur at very, very specific numbers. Core is really this 150 number, Dunbar’s number. But within that, there are a series of layers at 50, 15, 5 and the smallest one, 1.5.

And then beyond the 150 going out further, there are layers at 500, 1,500, the last possible one is 5,000 because 5,000 identifies the number of faces you can say whether you’ve seen them or not before. In other words, it’s the distinction between a complete stranger. I’ve never seen that face in my life and somebody you’ve seen but probably, for most of them, you don’t know much about. You don’t even know their name maybe.

But then the 1,500 layer within that, which actually turns out to be the typical size of tribes in hunter-gatherer societies. The distinction there is that you can put names to faces. As you come further in the 500 layers, the layer of acquaintances, many of the people you work with will be in that layer. In other words, you might go and have a beer with them after work. You might even spend a weekend away for some big work-related project with them, but you would never invite them back to your home for a big party.

Your 150 layer, well, that’s what I always call your bar mitzvah, weddings and funeral party. These are the people who will turn up out of obligation to you on that big once-in-a-lifetime event. You may not know they’re there in the third case, the funeral party, but believe me, they will be there. And then as you come in lower, so the relationships getting stronger and stronger.

The 15 layer is your sympathy group, people who you would feel extremely upset about if they die. That’s been known for a very long time. I didn’t discover that. And then inside that is this layer, five is the number’s layer, which is what we call the shoulder to cry on friends. And that layer turns out to be very important for you. It usually consists of two family members and two friends plus an another one per my design.

That number turns out to be the one that has the most influence on your general health and well-being. So the best predictor of your mental health and well-being, your physical health well-being, and even how long you’re going to live into the future from today is predicted by the number and quality of friendships you have in that layer. The five is an average. So if you only have three don’t panic yet, because introverts tend to prefer to have fewer people but have stronger friendships. As a result, extroverts tend to prefer slightly more people but have weaker friendships, those kind of effects. But on average, very much five. So as I’d like to say, if you really want to live forever, just make sure you’ve got five friends.”

Above diagram via Robin Dunbar, from his book ‘Friends’.

Patrick: And what about the 1.5. That seems like an odd number at the end of the cycle.

Robin: I always use to sort of come out with this joke when I was giving talks because I actually thought it was a joke, which was, well, just look at these series of circles and how very tight, the kind of fractal mathematical structure is. Each layer is three times the size of the layer inside it. And remember, these layers count cumulatively. So your 150 layer includes the 50 people in the layer inside. It’s not an addition. But just look at the regularity of these structuring, of these numbers, and surely, there’s a layer missing, if you project backwards.

Because you only knew about the five, we thought the five is the smallest number. If you project backwards, there’s a number missing and what is it? Well, it’s 1.5 and everybody would say, “How can you have 1.5 relationships?” The answer is obvious think about it. Half the population has one very, very close friend in that circle. And the other half of the population has two, what might the difference be? Well, the answer is gender. It’s obvious.

And the question is, why are women having two? And the answer is they have a platonic friend called the best friend forever. BFF. And that’s nearly always another woman, not 100%. 85% of women at any one time, have a best friend forever because the social psychologists who’ve explored this question have told us that constant reason that women always hear this because their romantic partner who statistically, obviously, is usually a male is completely useless at emotional-ish. You need somebody else who’s better qualified to deal with the emotional issues to sort of deal with that part of your life and the only person that falls into that little bracket as it were, is a girlfriend. The average is the male’s one and the women’s two that makes the 1.5 of that layer.

The layers are created by essentially the amount of time you spend doing stuff with different people. So obviously, the inner core layer, these layers in your social network have very specific frequencies of interaction you must have to keep the person in that layer. So the people in your five shoulder to cry on friends layer, you have to see at least once a week. That’s the minimum. The people in the 15, sympathy group layer next outside that you have to see at least once a month. If you see them less, those relationships decay inexorably.

It takes about 3 years for somebody to go from being a member of your 15 sympathy group to falling out of your 150 and joining the layer of acquaintances, which includes your favorite barista that you get your glass of coffee from every morning on the way to work and that kind of thing. So you have to invest time in relationships in proportion to essentially the emotional closeness. And it turns out that emotional closeness of a relationship is highly correlated with the time you invest in it.

Patrick: I’m so fascinated that I think in your research, you show 60% of people’s time they spend with maybe 40% with the closest five and another 20% with the next 10. Time it just strikes me is the resource. It’s the resource that we have to allocate thoughtfully and building those groups, time is the only way to do it, conversation and activity.

5/ David Senra on Jensen Huang’s whiteboard obsession

Link to podcast.

Enjoyed this episode by David Senra where he looks at Jensen Huang’s life through Tae Kim’s book ‘The Nvidia Way’. Lots of interesting snippets that give you a glimpse of how Jensen Huang thinks (a lot closer to Steve Jobs in a way) and acts. A good glimpse into high strategy, especially how to create the conditions and environment that sets you to win. Read ‘Three Teams, Two Seasons’ segment in the excerpts linked to below, to get a glimpse of this. Oh, and fun fact: Jensen Huang has a favourite brand of marker that is sold only in Taiwan.

David: “Their first product, right, is a flop and it’s called the NV1. And so Jensen is actually doing like this postmortem, and he realized they made several critical mistakes with the NV1. So I’m going to read a section from the book to you. Some of these critical mistakes with the NV1 start from positioning to product strategy. He says they had over-designed the card, stuffing it with features no one cared about. The market simply wanted the fastest graphics performance for the best games at a decent price and nothing else. The NV1 could simply not stack up against other cards that were more narrowly designed.

This is what Jensen said: “We learned it was better to do fewer things well than to do too many things. Nobody goes to the store to buy a Swiss Army knife. It is something that you get for Christmas.” Says—this is what James Dyson said: “People do not want all-purpose. They want high-tech specificity.”

*

David: “Some people like Bezos wants a six-page memo. Jobs wants a demo. Jensen wants the whiteboard. So the whiteboard represents both possibility and ephemerality. I can’t pronounce that word, I’m sorry. The belief that a successful idea, no matter how brilliant, must eventually be erased and a new one must take its place. One of the reasons Jensen likes to use the whiteboard as the primary form of communication in meetings is everybody must demonstrate their thought process in real time in front of an audience. With the whiteboard, there is no hiding. I lost count how many times in the book they’re talking about how central, like, how important whiteboarding is to running NVIDIA.

And actually, one of the things that Tay Kim was gracious to send me, he sent me this Wall Street Journal write-up, a review of the book written by this guy named Ben Cohen. Ben has some great writing here in terms of like what he learned from reading the book and the importance of the Whiteboard. It says, “Instead of cloistering himself in a private office, Jensen prefers to work from conference rooms. He does his best thinking at the whiteboard, which he uses so frequently that he has a favorite brand of marker that is only sold in Taiwan.” And so even when he’s traveling, they have to travel with this specific brand of marker, and they have to travel with whiteboards.”

Link to excerpts from the podcast I found interesting.

6/ Nabeel Qureshi on how the best talent brands are polarising

Link to the Lenny Rachitsky Podcast episode.

Good podcast episode spurred by his recent piece on his experience at Palantir – it covers his time at Palantir as a Forward Deployment Engineer, his new startup, and some interesting book recommendations; Impro, which is one of Palantir’s recommended reads, gets a mention, as does Shakespeare’s Henriad(!) and Anna Karenina!

From the podcast episode, I thought this comment by him on how the best (recruitment) brands are polarising, was interesting. The best recruitment brands per Nabeel, push away some people as much as they pull forward certain people.

Nabeel S. Qureshi: “There was also the question of, I think it might have been Thiel who mentioned this, but he thinks that a lot of the best recruiters in the world or the companies that attract talent, they put out this distinctive bat signal and it has to turn some people off. That’s the key of a good, bat signal.

So, I think in the present day, OpenAI and Anthropic, they’re both sucking up some of the best talent that you and I know. And I think one way they do that, and they are sincere in this, but they do really attract people who are almost messianic about the potential of artificial super intelligence and who really believe this is the only thing that matters and it is going to be the biggest thing in the world.

I think Palantir’s version of that was that they were quite focused on things like preserving the West. There was a slogan of Save the Shire, right? So, they were talking about military and defense and intelligence and the importance of that well before everybody else.”

7/ David Senra on Todd Graves’s Raising Cane’s, and focus

Link to Founders Podcast episode.

Todd Graves runs a fast-growing fast food chain with a limited menu focused around Chicken Fingers! David Senra mentions him as a living entrepreneur who he admires greatly. In this podcast episode, he covers why. I thought this passage (below) was particularly good.

“Charlie Munger has his great line, something to the effect that oftentimes in winning, the business system goes ridiculously far by minimizing or maximizing one or a few variables. And he used Costco as an example. And so the clip that I saw was Todd saying that he has this very simple menu, the same menu that he’s had since day one. He had all these people tell him, before he started the business in its early years, that, to this day, what you’re doing is not going to work.

Your menu is too simple. You need to follow the trends; you need to do what your competitors are doing. And he stubbornly believes in doing one thing and doing it the best you can. So he says, “I’ve always believed in doing one thing and doing it better than anybody else.”

If you do what you do well and consistently do it great, your customers will come back. And so, if I add different items to the menu, I wouldn’t be as quick in the drive-thru; if I overcomplicated things, my quality would go down, my speed would go down, and it wouldn’t be our concept. Adding different things and losing focus would make us less special. And so it’s not just that if I narrow the focus and perfect every single detail, I will create the greatest product in my category, but he also understands how everything he does relates to the entire system.

So this idea is like, if I have a simpler menu that makes my product better because I can really focus on it, right? But it means that people come through the drive-thru or into the store. And because they’re. You have four things.

You go into Raising Cane’s, right? You’re like, do you want three chicken fingers? Do you want four or do you want six? It makes you order faster.

And so why is that important? It may not make a difference when you have one or two stores if you save 15 or 30 seconds for each order. But it makes a hell of a difference, right, when you have 800 stores, like he does today. “

We see that

Focus (limited SKUs) help you create a better product

Limited SKUs / focus also helps the enabling support mechanisms or other interconnected mechanisms work better (like here fewer SKUs = faster ordering at the drive thru, and hence quicker turnaround)

The big Indian brands that exemplified this thus far have been DMart, Indigo (give me more examples, i collect these). This is also something that I frequently share with the founders I meet, but it is very very hard for me to get the message through:)

8/ Hunter Somerville, Stepstone, on How I Invest

Link to ‘How I Invest’ podcast episode.

This passage from Hunter Somerville of Stepstone, a leading fund of funds in the venture world, on how they track potential emerging managers was fascinating to me. This is exactly how a GP / fund would use Harmonic et al to track potential founders.

Hunter Somerville: When you see someone leave an established brand and start a new organization that has done all of that, sophisticated LPs that are active in venture move pretty quickly and those fund raises happen in very short time frames. Where I think emerging managers are in more jeopardy are when it’s someone that’s a mid level person that’s never run an organization that has a body of work that maybe they sourced but they didn’t cover, they didn’t sit on the board of, or operators that have never invested before, don’t have an investment track record, or have done very tiny angel checks that are just not indicative of their ability to execute as a lead or a number two in seed rounds going forward.

…

Hunter Somerville: You can’t fully anticipate spinouts. You can look at organizations and know where there’s dysfunction or where you think that it’s going to get worse, where you know economics aren’t being distributed appropriately or where there are people that are hanging on too long.

Hunter Somerville: We know those firms, we know where we think it will happen. And there we dig in even further on people’s bodies of work and track records in case it does happen. But as an organization within our venture group, we are tracking attribution and performance for every individual within the funds that we’re in. And the fortunate position we find ourselves in, we are in over 300 venture and growth managers to begin with.

Hunter Somerville: And that allows us to get the data on what each individual partner is doing, the roles they’ve served in sourcing and coverage, in value add post investment. And we compile all of that and go through it as a venture team on a quarterly basis where we look at the rising performers, who’s doing well within those organizations, who we may have not appreciated just from like a diligence effort when you’re spending time with the manager and who’s had really good follow on activity in the investments that they’ve made. And we start building narratives among our team, both as we assess that manager and as we consider whether there’s spin out potential from specific individuals within that manager. And that creates the prepared mind that I was talking about in case something does happen and becomes catalyzed and we then try to move pretty quickly.

Because not only would we like to be active in backing those groups, but we’re very happy to be an anchor and the first group to commit. We don’t need social proof. We don’t really care about that. And we want to be part of the journey with those managers from the very beginning and help them think through building a great organization and picking the right LP partners, which as I mentioned before, is a huge intrinsic risk if you don’t do it.

The episode is a good listen for any aspiring GP / fund manager. Link to excerpts from the podcast I found particularly interesting here.

9/ David Senra on Les Schwab, on the second order effect of incentives

Link to Founders Podcast episode.

Senra: Charlie says over and over again, never ever think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives. Multiple times in Poor Charlie’s Almanack, you see ideas just like that. Incentives rule everything around you.

Never ever think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives. The most important rule in management is get the incentives right.

…

Les Schwab: “This is how more on how we set up the corporation at the very beginning. Each store operates as a separate entity and each store operates as a separate business. The store employees share only in the profits of the store they work in.”

Senra: Let’s go back to the fact that incentives drive behavior. One benefit, one unexpected benefit of sharing profits with employees, less theft from within. Again, never ever think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives. He’s talking about the fact that they will expand.

I think at this point, they have 163 stores and people would analyze this company like where are all your controls? And he’s like, “Well, we don’t have any controls.” Why? Because the incentives are controlling behavior. “We didn’t have many controls. So the thing that held it together was that we ran each store as a separate entity. As long as we made sure that every tyre was billed to them, as long as they made sure that every tyre they sold was billed to the customer, we would come out all right.

10/ Bill Shufelt, Athletic Brewing, on doing things that don’t scale

Link to The Logan Bartlett Podcast episode.

A bit late to this enjoyable episode where Bill Shufelt, hedge fund operator turned cofounder of non-alcoholic beer co, Athletic Brewing, speaks to Logan Bartlett. What I found interesting was how the rising use of wearables, and the increased awareness that comes with it of key markers in the body and how they react to sleep / drinking, creates a forcing function almost against liquor. That was one, and the other was interestingly around doing things that don’t scale in the early days, and how it compounds.

“Logan: As I reflect on like health trends have been moving in a good direction for a long time. And there’s probably. Some element of like the increased wearables. I’ve two on my hands right now. And it becoming self, I mean, listen, these things are such snitches. If you have like a drink the night before, it’s like they know, and they yell at you. And my bed yells at me. I get yelled at every direction. So I have to assume that was like one of the things as well.

Bill: I mean, the nice thing is like when I showed up in my physical this fall, like an annual physical, I was showing up with not only data from my watch and wearables, but like my pre Nuva scan. And like, I was like, this is all the factual information about what’s going on in my body. And like, That just didn’t exist 15 years ago.”

*

“Bill: I don’t know what the customer acquisition cost of spending 10 minutes talking to someone at a booth that I’ve driven six hours to be at is,

Logan: Probably high.

Bill: it’s not great, but like I can’t tell you how many events I’ve done and I’ve gone back to like three years later, like a trail half marathon that I haven’t been at since 2018 people have been like, I met you in 2018 and my fridge has been full of your beer ever since, or like, and in my head I’m like, that’s easily a thousand LTV customer. And um, so I think like you said, scalable before, and I’m a big fan of these like unscalable activities if we do enough of them over and over again, like those scalable activities all of a sudden you turn around and you’re like, Oh wow, we activated 3 – 500 events.”

Link to excerpts from the podcast I found particularly interesting here.

Some more podcasts I liked but haven’t extracted excerpts from

Howard Schultz, Starbucks, on the Acquired Podcast. Late to this terrific podcast episode featuring Howard Schultz, the founder of Starbucks talking through the early, and more recent, history of Starbucks, including the decisions around going Global, expanding the menu etc.

Victor Shih on the Dwarkesh Podcast. Victor Shih, China watcher at UC San Diego; gives a good rundown / view into the internal machinations underlying Chinese political structure, and how policy gets made.

Anton Howes, historian, on the Ideas of India podcast. Fascinating podcast episode, covering how salt taxes and policies around that by the East India Company led to the death of hundreds of thousands of Bengalis and also led to malnutrition and long-term economic malaise (fascinating to read about the great hedge of India, a customs barrier that covered the length of India from Punjab to Bengal to ensure salt wasn’t smuggled). I also did not anticipate that several European conflicts were really salt wars.

Chris Arnade, urban walker, on Conversations with Tyler. Particle-physicist turned Hedge Fund operator, turned walker of cities, Chris Arnade, walks cities, and blogs on them. Through these walks and in the subsequent essays he posts on his substack, he explores urban life, culture, sociology etc. This episode was really interesting.

Bye!

It is time to wrap this! As I shared earlier, you should think of this substack as akin to a monthly magazine - you don’t have to read it all in one sitting, and you don’t have to read all of it!

That is all for now folks. Feedback, or your own ruminations, in the comments or at sp@sajithpai.com (Please don’t send pitches or CVs or anything work-related at my personal id; I won’t respond to them).

I picked up Alpha Girls after reading your LinkedIn post/tweets! Loving it. Might even write a review soon.

Thanks for sharing this, Sajith — I completely agree that writing consistently only about what truly sparks your curiosity is what sustains the long game. That’s how you build a durable audience and avoid burnout. Infinite games, indeed.

Related piece from my own archive: Why Consistency Wins in PR: Building Trust One Story at a Time